By Christina Cavazos

A family that loved the outdoors, the Haras took vacations to places like Arkansas and North Carolina where they’d canoe and spend time exploring the natural landscape. However, they never did those same activities at home on the river that they traveled over every day.

Its brown water nestled between muddy, red clay embankments adorned with pine trees and hardwoods, the Sabine River wasn’t thought of as a place for recreation. In fact, it wasn’t really thought of at all. In 2019, well into adulthood, he took his first trip on the Sabine River with a small group of friends. That’s when he realized just how beautiful the river really is and all the potential that it holds.

“You’re only a couple of miles away from Longview, but it feels like you are miles away because you’re just completely in the East Texas Piney Wood forest,” he said. “There’s a beauty there that you don’t always expect.”

In the last five years, the number of people who enjoy traveling the river has grown exponentially as more individuals come to know the true beauty of the river. Now community leaders are considering options to improve access to the Sabine so that a river that was mostly overlooked for more than a century has the opportunity to become a place of recreation and tourism.

“Part of the goal is to have an additional recreation opportunity that is accessible for visitors and for locals to be able to go and enjoy.” Hara said.

The River

Archaeological evidence shows the Sabine River has been inhabited for more than 12,000 years to when, according to the Texas State Historical Association, the Clovis tribe, an ancient culture in North America, lived there. The Caddos likely arrived in the area by about the year 780 A.D., according to the state historical association. Early Caddo mounds have been discovered along the river. The Caddos culture flourished until the late 13th century.

Europeans arrived in the area in the 16th century. In 1716, Spanish explorer Domingo Ramón gave the river its name, according to the Texas State Historical Association. The name Sabine River, or Río de Sabinas, comes from the Spanish word for “cypress” as cypress trees are prevalent along certain portions of the river.

Sabine River Fast Facts

- Three forks of the Sabine River that start in Collin and Hunt Counties merge in Lake Tawakoni to form the Sabine River proper.

- The river flows for about 580 miles. From Hunt County it flows southeast to Panola County where it turns south and flows until it discharges in Lake Sabine at the Gulf of Mexico.

- The Sabine River discharges more water than any other Texas river into the Gulf of Mexico.

- Spanish explorer Domingo Ramón gave the river its name. The name, “Sabine” comes from the Spanish word for “cypress.”

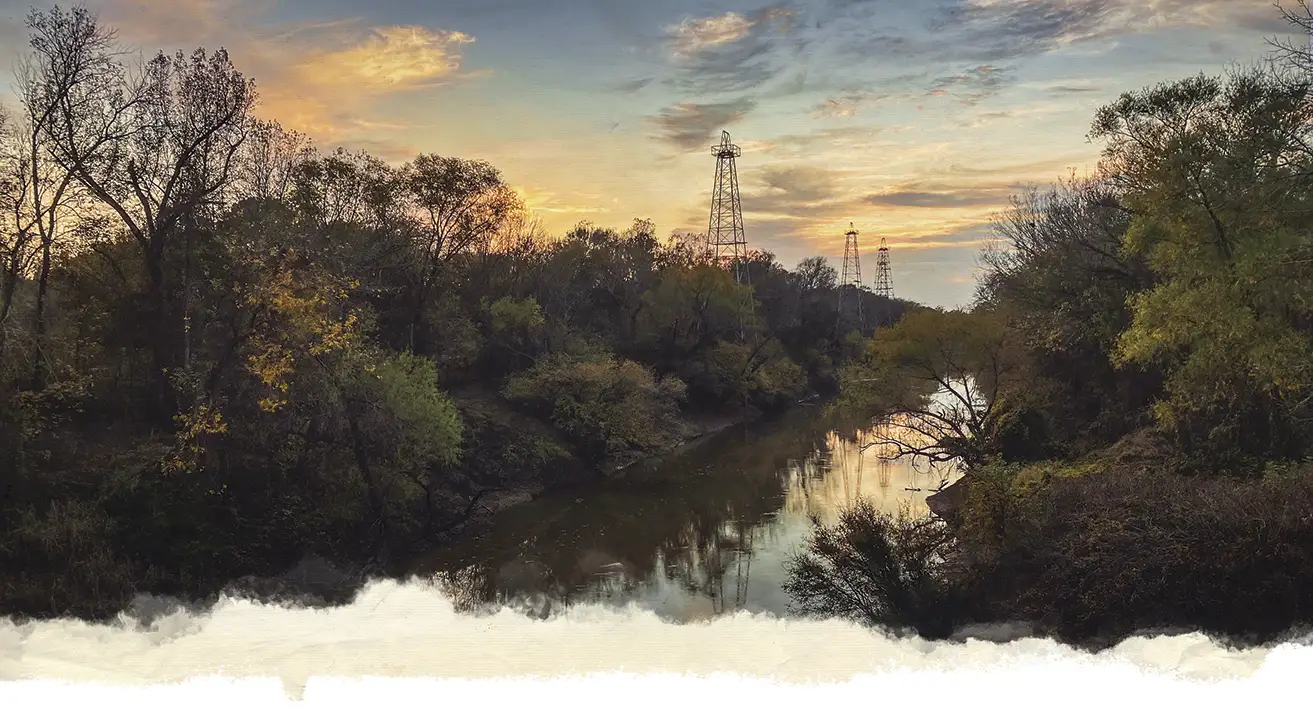

When standing at the river bridge on a clear day, the scenery is iconic to East Texas. Oil derricks stand tall amid pine trees with the water of the Sabine River flowing below.

The river starts just south of Greenville at Lake Tawakoni where three forks merge. Those forks originate in Collin County and Hunt County, respectively, and converge at Lake Tawakoni to form the Sabine River proper. The river flows southeasterly from Lake Tawakoni to the southeastern corner of Panola County where it turns and takes a southern course. It empties into Lake Sabine at the Gulf of Mexico where it has the largest water discharge at its mouth of any Texas river, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

The approximately 580-mile-long river forms the boundary lines between several counties — Rains and Van Zandt, Van Zandt and Wood, Wood and Smith, and Smith and Upshur. When Gregg County was founded in 1873, the Sabine River served as the original southern boundary; however, in 1874, Gregg County acquired the northern portion of neighboring Rusk County as it extended its area. When it turns south in Panola County, the river also forms the border between Texas and Louisiana.

Throughout history, the river served as transportation for cotton and lumber; the basin was the site of logging operations; and many sawmills were built along banks. After the oil boom, the river basin became the site of large-scale oil exploration and led to growth in the oil industry.

In East Texas, the oilfield dates back to 1930 with off-shore drilling expanded to the Sabine River in 1932. Today, many oil derricks remain along the river and in 2011, the Texas Historical Commission placed a marker along the Sabine River at Texas 42 and River Road, cementing the river’s place in East Texas’ oil history.

When standing at the river bridge on a clear day, the scenery is iconic to East Texas. Oil derricks stand tall amid pine trees with the water of the Sabine River flowing below. While thousands of people travel over the bridge each day, few stop to get on the river and explore its unique beauty.

There are many reasons why people don’t stop to explore the Sabine.

For one, there are limited access points, which is something local leaders want to improve, but there’s also public perception of the river, which in some ways has to overcome a longstanding local stereotype of itself.

When Hara was growing up, he said, the perception of the Sabine was “always very negative.” It was often described as “dirty” and “dangerous.”

The Sabine River doesn’t have crystal clear waters, and it’s never been a local swimming hole. Instead, its waters typically take on a brownish hue as do several other rivers in Texas. That hue is caused by several factors, but predominantly the fact that as rivers flow south toward the gulf, they pick up sediment and soil, like East Texas red clay, which affects the color.

Meanwhile, the river has few access points and mostly flows through undeveloped areas. That means when you travel on it, it can feel like you’re isolated from the rest of the world even if you’re only a couple of miles outside of the city.

Paddling the Sabine

For those who enjoy exploring the outdoors, that feeling of being miles removed from the city is often something to be appreciated. It was 2019 when Hara first began to question why he’d never been on the Sabine River, so he put a float together and then another, and it continued to grow as more people joined in.

“Along the way, we have met a lot of people who share a mutual interest for the river,” Hara says. “Some have been already using the river for recreation for many years and others had been wanting to do so but didn’t know how to access for kayaking.”

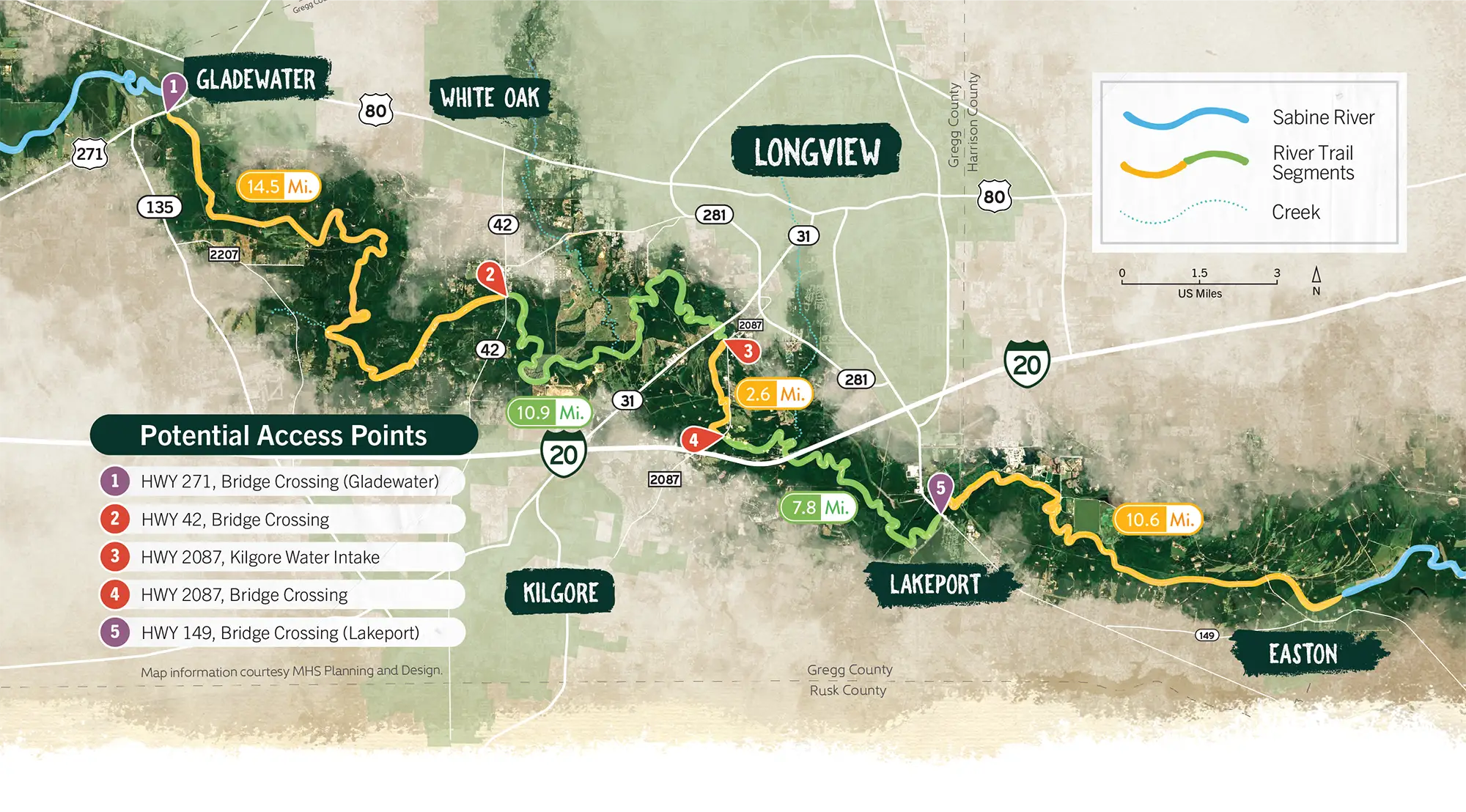

Hara said it took a while to figure out how to make the trips happen because there are few public access points along the river. In Gregg County, there are two public access points, but they’re forty river miles apart. One is in Gladewater at U.S. 271; the other is in Lakeport at Texas 149. Hara knew he and his travel companions couldn’t paddle forty miles in a day.

For one trip, he and Keith Bonds decided the group could start at the Gladewater access point and get out fourteen miles later at The Sandbar, a small bar located right off the Sabine on River Road. There is a tall, rusty staircase that can be used to get out of the water at the bar, so that’s exactly what the group did.

“This was October 2019. So we get out there and the river was really low, and there was no flow, so we paddled the whole way,” he recalled. “By the time we got to the end, we were all just dead tired. We pulled our kayaks up these tall stairs, and then we ate at the Sandbar. And I thought, well that was fun.”

As he began coordinating trips along the Sabine with different entrance and exit points, Hara said it’s been interesting to meet individuals who have used the Sabine River for recreation for years. Despite limited access points, there are still many others – like him – who enjoy what the river has to offer.

For his trips, Hara occasionally works with private landowners to arrange an entrance or an exit point from the river. Some trips have been eight miles or fourteen miles, and some have necessitated an overnight stay.

The number of people joining the excursions has also grown and annual “Floatsgiving” trips offer an opportunity for friends to get together and float the river amid the hustle and bustle of the holiday season.

“The thing that I’ve really enjoyed is putting together these groups and seeing other people going down and seeing the river and exploring it and enjoying being down there,” Hara said.

Each time someone new joins a float, Hara said he enjoys hearing their experience afterward.

It’s often not what they thought it would be – the Sabine River defies the stereotypes the locals have given to it. Instead, people often are mesmerized by the natural beauty as they float along the river amid the Piney Woods.

“Probably one of my favorite moments was when we got to see bald eagles,” Hara said. “There’s a spot just down river from Highway 42 where there was a bald eagle nest. That was really neat. That discovery was cool.”

He also recalled a trip along the river with his wife, Bethany, when they found “huge” freshwater clam shells. “I just had no idea that kind of thing would be there,” he said.

Meanwhile, with East Texas’ oil history, there’s a section of the river between Lakeport and Tatum where there’s an abundance of lignite shoal. “There are these cliff walls that are basically all lignite so it’s like this gleaming black wall as you go by,” he said. There are also a few white sandy beaches along the river. The Sabine is full of surprises.

Texas State Paddling Trails

In organizing the floats, Hara began researching Texas Paddling Trails. A program of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas Paddling Trails are designated trails where the public can canoe and kayak.

In the Piney Woods, there are several trails. There are ten designated trails at Caddo Lake and Big Cypress Bayou in the Jefferson-Karnack area. In Carthage, there’s the Sabine Sandbar Paddling Trail which offers four, fifteen, or nineteen miles of paddling trail. In Mineola, the 11.9-mile Mineola Bigfoot Paddling Trail invites visitors to traverse that portion of the Sabine River. Meanwhile, there are several designated trails along the nearby Neches River in the Athens, Tyler, Jacksonville areas.

There are criteria in place to become a paddling trail.

“You’ve got to have public access points and parking; you’ve got to have amenities nearby. It has to be somewhat close to a community, and you have to have trails that would be between four miles and twelve miles in distance,” Hara said. With the nearby publicly owned ramps being forty miles apart, Hara began to wonder if there might be opportunities for other public access points.

In Longview, the Sabine River is one of three water resources for public drinking water. The others are Lake Cherokee and Lake O’ the Pines. Like Longview, Kilgore also draws some of its water from the Sabine.

Hara reached out to the City of Kilgore to see if it might be interested in exploring the paddle trail program. It was. Soon, Gladewater, White Oak, Lakeport, Easton, and Gregg County itself had also joined in.

“When I called Kilgore, their staff had already also been considering a river access effort. Similarly, in Lakeport, they were already very interested in how to improve the river as an amenity in their community. So, it was a good opportunity for collaboration.”

The county applied for and was awarded a grant by the Sabine River Authority to study improving access to the river for recreational usage as well as emergency response. Gregg County contracted with MHS Planning and Design for the study.

An Underutilized Resource

MHS conducted a study to review access exploration to the Sabine River throughout Gregg County. The study area went from Gladewater to Easton, revealing twelve potential access points along the river.

The overwhelming message, Hara said, is that the Sabine River through Gregg County is “an underutilized natural resource.”

John Waltz, a planner with MHS Planning and Design, said the company’s research was a combination of physical tours as well as planning sessions and soliciting feedback from the community.

The team compiled a list of strengths and weaknesses as well as areas for opportunity. Waltz said strengths include that the Sabine provides a water resource to several communities in East Texas as well as that the project has strong local support and diverse wildlife prevalent in the area. Weaknesses included lack of safe general access, high banks that limit emergency access to the river, and occasional log jams that require strenuous clearing efforts.

Opportunities or goals of the project, Waltz said, include increasing recreation and public wellness access as well as potential to draw untapped tourism into the area.

“Kayaking nationwide is increasing in popularity … We do want to take advantage of that growing interest in kayaking to increase public awareness of the region’s history,” he said.

With potential access points identified, the plan will continue to be fine-tuned. Once a plan is in place and access points are prioritized, it will still take time, fundraising, and development to see it come to fruition.

After public access points are increased, there is long-range potential for a state-designated paddling trail through Gregg County. That’s still likely several years away at least, Hara noted.

Hara said the Sabine River is ideal though for a future paddling trail. It’s easily navigable in the region, it’s beginner friendly, and there are not many rapids.

“The goal is to have an additional recreation opportunity that is accessible for visitors and for locals to be able to go and enjoy,” he said. “We want to make it be a natural resource that’s accessible and that other people can go, float, enjoy and see East Texas.”

As East Texas communities work together to research infrastructure development around the river, the unexpected beauty of the Sabine River will doubtlessly be discovered and spur further interest in the potential of this hidden gem.